Impeachment (thought I best cover this before it fades into the background......)

- tim@emorningcoffee.com

- Jan 13, 2020

- 7 min read

Updated: Jul 19, 2020

The good news about the current impeachment process - if there can possibly be any - is that it reminds the US electorate of how this once-in-a-century process works. Impeachment exists primarily to protect the integrity of the offices of certain elected officials, including the President of the United States.

I will start this post by admitting that the “once-in-a-century” comment in my opening sentence is not exactly true, since President Nixon resigned in disgrace in 1974 under threat of impeachment, President Clinton was impeached in 1998 but acquitted by the Senate, and President Trump has now also been impeached by the House (apparently though unofficially since the impeachment has not been sent to the Senate). But there was indeed a lot of time between the impeachment of Clinton in 1998 and the last president before Clinton subject to impeachment proceedings, Andrew Johnson, in 1868. With the infamous trio of Nixon, Clinton and now President Trump all impeached (or threatened), it seems clear that US presidents have been more willing to “take the low road” during the last 50 years, or U.S. politics has simply become more and more partisan, or – most likely – a combination of both. But let’s quickly get back to the current proceedings.

When can a US public official be impeached? This extract is from the January 1867 (yes, the date is correct) of The Atlantic, which describes the reason the Constitution provides for impeachment:

“The Constitution provides, in express terms, that the President, as well as the Vice-President and all civil officers, may be impeached for “treason, bribery, or other high crimes and misdemeanours.” It was framed by men who had learned to their sorrow the falsity of the English maxim, that “the king can do no wrong,” and established by the people, who meant to hold all their public servants, the highest and the lowest, to the strictest accountability. All were jealous of any “squinting towards monarchy,” and determined to allow to the chief magistrate no sort of regal immunity, but to secure his faithfulness and their own rights by holding him personally answerable for his misconduct, and to protect the government by making adequate provision for his removal. Moreover, they did not mean that the door should not be locked till after the horse had been stolen.”

How does the impeachment process work? Here are the steps:

A judicial sub-committee of the House of Representatives listens to and evaluates evidence supporting impeachment. This evidence is then used as the basis for a set of charges, or “articles of impeachment”. The articles of impeachment are referred to the members of the House for a vote. A simple majority in favour will result in the president being impeached. The impeachment is then referred to the Senate for a “trial”.

The Senate considers the evidence in a “trial” overseen by the Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court. In the current case of President Trump, this will be Chief Justice John Roberts. Once the evidence has been presented to the Senate, the charges are considered and voted on by the members of Senate. It takes two-thirds super-majority to convict a president. (Note that although both Johnson and Clinton were impeached by the House, both were also acquitted by the Senate.)

History has shown that the impeachment process from House to Senate is not a legal process or trial. Rather, it is an entirely political - and hence partisan - process.

My last time through an impeachment process involved President Clinton, who was impeached by the House but acquitted by the Senate. The expectation by most is that the impeachment of President Trump will likely end up the same way. This article “Trump impeachment inquiry: The case for and against” from the BBC presented a balanced approach on the proceedings, including the case against the President and evidence in support of impeachment, with comments by several recognised legal scholars. From my perspective, I must say that the substance of the allegations in favour of impeachment seems fairly straight-forward and convincing, but at the same time, it is clear that the evidence can be interpreted as inconclusive because the meaning of “treason, bribery, or other high crimes and misdemeanours” is often ambiguous at best.

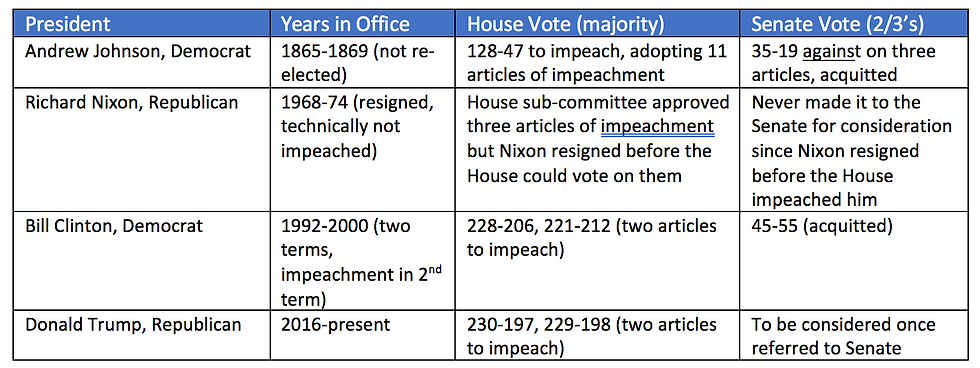

As I already mentioned, the process is highly partisan. Here’s how the other impeachment cases involving U.S. Presidents have ended:

Without going back in time and just looking at current proceedings against President Trump, the votes for impeachment (two charges – abuse of power (230-197) and obstruction of justice (229-198) - were clearly along partisan lines:

Abuse of Power: 230 in favour consisted of 229 Dems and 1 Independent; 197 against consisted of 195 Reps and 2 Dems

Obstruction of Justice: 229 in favour consisted of 228 Dems and 1 Independent; 198 against consisted of 195 Reps and 3 Dems

For reference, the House of Representatives currently consists of 232 Dems, 198 Reps and 1 Independent (and 4 seats vacant).

The Senate – which currently consists of 53 Republicans, 45 Democrats and 2 Independents - requires 2/3’s super-majority vote in favour to formally remove the president. It seems clear to me that the Republicans in the Senate will dig in their heels, and they have said as much. Therefore, it is highly unlikely that there will be 67 Senators in favour of the removal of President Trump. To convict President Trump of these allegations would require not only all of the Democrats to vote in favour, but also both independents in the Senate and 20 Republicans. Unless something else more sinister (as far as evidence) emerges, President Trump will be acquitted by the Senate. Remember – this is not a legal trial, but rather a highly political and partisan process. It is déjà vu for those that were around and followed the Clinton impeachment proceedings, another example of American partisan politics at its finest.

Let’s look past the likely Senate acquittal, and ask the really important question: “has this process hurt or helped the Democrats in this critical election year?” This is likely to be left in the hands of the centre of the electorate, meaning the more centrist elements (or one might say the “more open-minded” members) of both major parties, along with those voters that are non-partisan and independent. Why? Because I suspect the impeachment proceedings have hardened the left of the Democratic base (“obviously guilty”) and the right of the Republican base (“not at all guilty as there was no clear quid pro quo”), so let’s just say the hard core base of each party (perhaps 30-35% in each case) will not be swayed regardless of the likely Senate acquittal. This means that the election will likely be down to the 30% to 40% of mailable voters in the middle that will consider the impeachment proceedings (amongst other issues on the platforms of each party) to formulate an opinion as to the fitness of President Trump - and more broadly the Republican party - for a second term in office. And lest you forget my views on this, I believe that no one can pound the table and say that they are definitively right. We live in a Democracy and even if you don’t agree with the other side, everyone deserves the opportunity to develop and express their own view, and to vote accordingly.

The only anecdotal evidence we can study - for what it is worth - is the after-effects of the other Presidential impeachments, as well as the near-impeachment of President Nixon. In every case, the incumbent or the party of the incumbent lost the next election, as detailed below.

Andrew Johnson (Democrat), who replaced A Lincoln when he was assassinated; served from 1865-1969 and did not run for re-election. The Democrats lost the election in 1869 to the Republican candidate Ulysses S. Grant, who went on to serve two terms

Bill Clinton (Democrat), who served two terms (1992-2000) and was not eligible to run for re-election. Again, the Democrats lost the election in November 1999 to George W. Bush, the Republican candidate, who went on to serve two terms

Gerald Ford (Republican), who replaced Nixon upon his resignation in 1974. Although chosen as the Republican candidate in 1975 to run for a second term, Ford lost the election to the Democrat challenger Jimmy Carter, who served one term from 1976-1980

Perhaps in the current case, this anecdotal historical information means little because the “impeachment effect” might fade into the background as other issues are brought forward by each party during the run-up to the 2020 election. However, I cannot help but see the impeachment as a negative for President Trump. It is certainly not a positive, because the entrenched right of the Republican Party will vote for Trump no matter what he might add to his rather impressively long list of unsavoury attributes, while the entrenched left will vote against Trump even with a roaring economy and other “accomplishments”. It is the middle that will matter. And if you look at what has happened historically, even though the President has been acquitted in the prior two impeachments, the governing party has lost the subsequent election. (And the same was true when Nixon resigned on the doorstep of his impeachment.)

One more thing - even though principally a domestic political matter, we have to ask what these sorts of proceedings do for the perception of the U.S. abroad, since the U.S. remains the world’s sole dominant global power for the time being? As an American that has lived abroad for many years, I must say that the entire process looks a bit like a circus to most foreigners, although to be fair, it might not look that much different inside the U.S. Foreign governments undoubtedly see the U.S. impeachment process as a distraction for the Executive and Congressional branches of the U.S. government at a time when much more important things driving the everyday lives of Americans - both the domestic agenda and foreign affairs - should be on the table for debate and consideration. Let’s face it – the impeachment proceedings have grabbed centre stage, largely hijacking for now the law-making function of the U.S. government. In many ways, this is not much different than the three-year plus BREXIT discussions in the U.K. that more or less hampered Parliament from focusing on other more important issues. Fortunately, the page is about to be turned on the next chapter of BREXIT, and although not over, we finally have some clarity at least as far as the next step. Similarly, the U.S. impeachment proceedings can’t be over quickly enough so that the U.S. can move forward with its legislative agenda, and both parties can focus on their respective - and very different - platforms for the upcoming 2020 election.

Comments